Bringing the Bodega Back (Sherry) Part II

16 Sep

In Part I, I touched on some of what we learned from Katie Stipe and Phil Ward about the terroir in the Sherry Triangle and some interesting facts about the history of Sherry. This post will summarize some of the unique aspects of Sherry production prior to aging.

After recovering from the phylloxera epidemic, Sherry has been primarily produced using the white Palomino grape (90% of all sherry grapes) along with Moscatel and Pedro Ximenez grapes. The Moscatel and PX grapes are used for sweeter styles of Sherry and are laid out on grass matts in the sun for 12 days after picking to concentrate the sugars. These two grapes also go through a slightly different fermentation and aging process to that described below.

The pruning of the vines uses an interesting technique called “vara y pulgar” or “stick and thumb”. They train the vine to have two branches. Each year one is trimmed down to a couple buds (the thumb) and the other is allowed to grow out (the stick). This focuses all the energy of the vine into one branch each year and extends the productive life of the vine (30 to 35 years). Harvest, during which 75% of the grapes are still hand-picked due to the low vine height, is usually in early September and the exact timing is driven by the sugar level present in the grape.

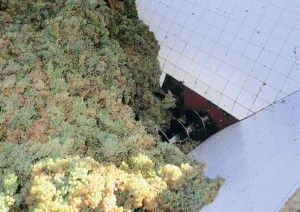

The grapes are crushed and optionally de-stemmed prior to extraction. There are two extraction presses, or “yemas”. The first yema utilizes light pressure and the composition of this grape must is more suitable for younger styles of sherry such as finos and manzinillas.

The second yema doubles the pressure, extracting more must from the solids and making it more suitable for the oxidative aging of the older styles of sherry. Any must resulting from pressing the remaining paste at higher pressure cannot be used for Sherry production.

Prior to fermentation, the must is clarified. Fermentation is done predominately in stainless steel. The first fermentation is usually instigated in a process known as “pies de cuba” wherein already actively fermenting must is added back into the new must. 95% of this “tumultuous” fermentation is completed in the first 7-10 days. The second, slower fermentation takes place over the following weeks as the autumn temperatures drop and the remaining sugars are converted to alcohol. The fermented must self-clarifies during this time as the lees (dead yeast) settles to the bottom.

As the lees settle to the bottom and are then removed, an indigenous yeast called “flor” begins to form on top of the fermented must. This yeast has very special characteristics. It has evolved to live off of alcohol and oxygen as well as unfermented sugars and other components in the wine. In turn, flor releases new components, most importantly acetaldehydes.

Since this yeast requires oxygen, fermentation is open and aging is done with the barrels or “butts” open. For ideal sherry aging, the butts are filled to no more than 5/6ths of their volume (“two fists of air”) to allow the flor sufficient oxygen. This also is why the bodegas were designed to hold high volumes of humid, circulating air. The name “flor” means flower, and this references the fact that the ideal temperature and humidity for flor growth occurs in the autumn and spring. Finally, flor only can live within a specific range of alcohol content. This will affect the style of wine that results when the producer fortifies it prior to aging.

Prior to fortification and aging, the wine is classified. To this point, the condition of the harvest, the location of the vineyard and its microclimate, whether the wine was first or second yema, and the process of fermentation have all contributed to creating a unique wine. Tasters now determine if the wine displays more finesse and paleness (usually 1st yema) or if they have a heavier, or “gordura” structure (usually 2nd yema) appropriate for oxidative aging. They accomplish this both through lab analysis and actual tasting. The first are categorized as finos, marked with a “/” and the second as oloroso, marked with a “O”.

The wine has reached 11-12.5% ABV due to fermentation. Hundreds of years ago fortification of Sherry was used to stabilize the wine for extended travel. However, after the Vintner’s Guild was abolished, the aim of fortification developed to become deterministic of the style of fortified wine produced through the two different Sherry aging processes. The wine the producer has determined to develop into either fino (/) or manzanillas will have neutral, unaged grape brandy spirit added to achieve 15.5% ABV. The wine destined to become oloroso (O) will be fortified to at least 17% ABV.

This decision has huge implications for the style of Sherry that will emerge from aging and recognizing this is important to understanding the complexity and diversity of Sherry. The fino or manzanillas will now undergo biological aging. The 15.5% ABV is such that flor will continue to develop but other microorganisms cannot. The composition of the wine will change biologically during the aging process but the flor film over the top will prevent changes due to oxidation. As Phil said, “This is the truth, nothing lies in here” … there is very little barrel effect or oxidation to change the inherent nature of the Sherry.

In contrast, at over 17% ABV even the alcohol loving flor cannot survive and biological changes cannot occur. Only oxidative aging is possible. The flor film will fade away and a slow oxidation will occur, hence the darker colors that result in these Sherries.

Part III will touch on the Sherry aging process, especially the Criadera/Solera system.

No comments yet