A Word on Column Stills

31 Aug

The column still is a pretty tricky device. A basic understanding of how it works is relatively easy to obtain. As I learned in Puerto Rico, even a slightly more technical understanding of the mechanics of one can be pretty elusive. We got a crash course from Don Q’s Liza Cordero, from which I walked away with many answers but a lot more questions. One thing I feel pretty confident about is an understanding of what some key differences are between the process of distillation via a column versus a pot still.

Distillation is a game of temperature differentials. What we want out of the process is concentrating one particular component of a liquid. Most often in our case this is alcohol. We know that alcohol boils at around 171 degrees, and all the other stuff in our mash each has it’s own distinct boiling point that is either higher or lower than that. Volatile compounds, such as higher alcohols, boil at lower temperatures. Heavier compounds such as fusel oils boil at lower ones. Which compounds stay and which get thrown our depend on the desired product, the opinions of the distiller, and the equipment used.

To caricaturize, a pot still is a game of timing. When heat is applied, the volatile compounds start to evaporate first. Then follows our precious alcohol. Finally, the heavier bits come through. How the distiller selects the desired compounds is through the means of a cut. The distiller throws out the first and last of the vapors off the still, leaving only what they’d like to keep to use in their product.

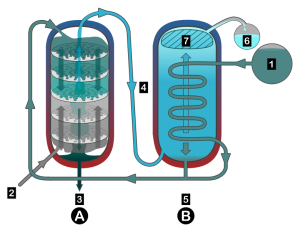

A column still is very different. One can select a given specific temperature, under or over which virtually all compounds will be discarded. The cut, rather than being a precisely timed act, is a decision made before firing up the still. In the column, the decision is made at each plate. To pick a relevant example, “does this particle boil above 170 degrees?” If so, it goes up. If not, it goes down.

The more plates there are in the column, the more of an accurate decision can be made. With a sufficiently large still, pure ethanol can be isolated in two steps*. First, get rid of everything below 170 degrees boiling point. Second, get rid of everything above 172 degrees boiling point. Simple, right?

This is where the nuance comes in. Like any advance in technology, there are perils. Pure alcohol isn’t what we’re always going for. Often, there are a lot of different things we desire for our end product. Accordingly, a column still doesn’t always result in a neutral spirit. In the right hands, it offers a much more sophisticated means of control over the distillate than any pot still ever could. And the amounts of flavoring compounds that find their way from still to bottle can be just as much, if not more than what one can obtain with a pot still.

With great power comes great responsibility.

*Alcohol and water love each other. No matter how big the still or how many times one distills, some degree of water will still adhere itself to the alcohol molecules and come through the still. It’s not really possible to get alcohol to hang out above 96% purity. This is why ever-clear isn’t 200 proof.

Wikipedia: S is the nineteenth letter in the ISO basic Latin alphabet. →

No comments yet