A Different Kind of Process

5 Jul

I can pinpoint the exact moment when I decided my blog topic reflecting our adventures of this trip. I’ve been on many distillery visits before, and I’m beginning to know the lay of the land pretty well. Any among us who are interested enough to read a detailed blog entry on the production of cognac can probably say the same. We can all spot a column still from a mile away, and have laid eyes on many a mashing tank.

When we entered the Frapin facility I had no idea what I was looking at. The closest thing to it I’d ever seen was a dressed up race car engine, except this was several times larger than the race car itself.

We’ll return to our mystery equipment in just a moment, but it was then I realized that cognac production differed from all other processes I had ever seen. And not just at points, but at every single step of the way. Let’s start at the beginning.

Cognac is one of two products that distinctively express terrior. Tequila is the essence of the agave, and Cognac of the grape. This alone makes it stand out in the world of spirits, but it doesn’t just stop there. The agave is a hearty plant which has evolved to thrive in adversity. It grows slowly and purposefully, storing up in times of plenty for times of lean. The grape is a different story. As we all know from wine, grapes are fickle and delicate. The hands of the grower are just as important as the soil and the rain.

The viticulture of Cognac is even divergent form normal wine-making practices. As it is often with distillation, a delicious product into the still sometimes means a bad product out the other end. The beer for most whiskeys isn’t particularly great on it’s own, and the apples used to make apple jack are ones we’d never remotely consider eating. For Cognac, the ideal wine is both high in acid and low in alcohol. The acid prevents the wine from spoiling, and the low ABV guarantees enough residual sugar.

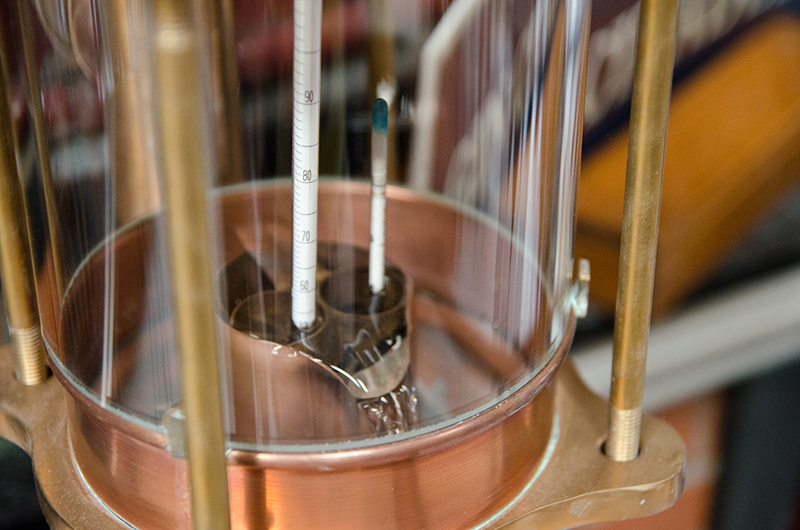

The wine making process starts off with my mystery machine, pictured above. I had never in my life seen an industrial grape press. Much of the machinery used before and during pressing is unique to handling grapes. This is a world apart from the familiarity of grain processing equipment that was around during my Midwest upbringing.

Distillation of Cognac is highly regulated. The stills must be entirely made of copper, which is a familiar sight. What wasn’t, though, was a thick red coating of paint. It appeared to be similar to an enamel coating, and it’s purpose is to prevent the corrosion of the exposed copper surface.

The next thing I noticed that was unique about the still was a giant vessel through which the swan’s neck ran before encountering the coil. My first thought was a thumper or a slobber pot, but the arrangement didn’t match that use. A thumper is a primitive device used to reuse the heat of distilling for the sake of efficiency, and it turns out this device is as well. The vessel is filled with the wine for the next distillation, and the vapor from the still warms it up on its way to condensation. It’s the same capacity as the still, and is in the perfect position to dump directly into the still for the next run.

That heat is, by law, produced by open flame. After the innovation of using steam to heat a still, Cognac producers made an active decision to only use an open flame to heat the wine. In years past this would have been provided by wood or coal, but modern operations rely entirely on natural gas for this purpose.

The ABV of the distillation is also regulated. The spirit must come off within a small range either side of 70% ABV. The reasoning behind this step is a bit of a mystery to me, but I’m sure the answer lies somewhere between deep tradition and quality control.

The last step of production for any brown spirit is aging. Far be it from the French to let even this part be easy. The moderately maritime climate of western France is definitely more similar to that of Scotland than that of the southern United States. We all know a more stable temperature range allows for longer periods of aging. The French take this a step further, controlling the type of wood the spirit sees, and under what conditions.

Cognac is traditionally aged in a damp cellar. In the muggy conditions, the air of the cellar is already saturated with water. This prevents the water in the spirit from evaporating, and causes the alcohol instead to precipitate out of the barrel. This is the exact opposite of a dry cellar, in which the angel’s share is mostly comprised of water. This is the reason that the proof of American whiskey raises during aging while the proof of Cognac often lowers. Cognac producers frequently use both types of aging, starting out younger eau de vies in new oak and dry cellars for faster exchange of tannins, then moving them progressively to damp cellars and older wood.

The type of wood used during aging is also very important. We all know that bourbon lives and dies by new oak. We also all know that the main reason for this was a savy ploy to create cooper and logging jobs. Regardless of the reasoning, new American oak is a the backbone of American whiskey. Sticking with their over-complication theme, the French process is much more complex. New French oak is often used on younger spirits, contributing it’s distinctive palate of vanilla, baking spice, and tannins. In this stage, the oak is doing all the work. Where things start to differ is in the use of older barrels for long-term aging. In this phase, the wood’s influence gives way to that of oxygen. As the spirit slowly oxidizes, simpler aromatic compounds break down into more complex and diverse ones.

In the extreme, aging can take place up to 70 or 90 years in oak. Older spirits gain more of what cellar masters refer to as ranceau. It’s a word derivative from the word rancid, and it is characterized by a musty, mushroomy, forest floor type aroma. When added to a blend, it’s presence is easily detectable in even small amounts. It adds a musty, savory complexity which helps to structure spirit with less age. After a certain degree, the spirit can suffer if it continues to oxidize any longer. At this stage it is removed from the barrel and stored in glass. This way even spirits from before pheloxera can still be preserved and used in very small amounts as a crucial component to blends.

Cognac is an incredibly beautiful, artistic, and crafted spirit. I’m sure some of the entries by my fellow students will help to flush out the intricacies of each step of it’s creation. For me, I felt the extreme expressiveness of the spirit and attention to detail in the process truly set Cognac apart from anything I had ever experienced before.

No comments yet